The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972. Colombia accepted the convention on 24 May 1983, making its historical sites eligible for inclusion on the list. As of 2018, there are nine World Heritage Sites in Colombia, including six cultural sites, two natural sites and one mixed site.

At present, Colombia has six sites included on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

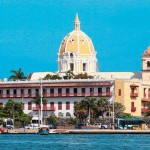

Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena de Indias

Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena de Indias

Situated on the northern coast of Colombia on a sheltered bay facing the Caribbean Sea, the city of Cartagena de Indias boasts the most extensive and one of the most complete systems of military fortifications in South America. Due to the city’s strategic location, this eminent example of the military architecture of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries was also one of the most important ports of the Caribbean. The port of Cartagena – together with Havana and San Juan, Puerto Rico – was an essential link in the route of the West Indies and thus an important chapter in the history of world exploration and the great commercial maritime routes. On the narrow streets of the colonial walled city can be found civil, religious and residential monuments of beauty and consequence.

Cartagena was for several centuries a focal point of confrontation among the principal European powers vying for control of the “New World.” Defensive fortifications were built by the Spanish in 1586 and were strengthened and extended to their current dimensions in the 18th century, taking full advantage of the natural defences offered by the numerous bayside channels and passes. The initial system of fortifications included the urban enclosure wall, the bastioned harbour of San Matías at the entry to the pass of Bocagrande, and the tower of San Felipe del Boquerón. All of the harbour’s natural passes were eventually dominated by fortresses: San Luis and San José, San Fernando, San Rafael and Santa Bárbara at Bocachica (the southwest pass); Santa Cruz, San Juan de Manzanillo and San Sebastián de Pastelillo around the interior of the bay; and the formidable Castillo San Felipe de Barajas on the rocky crag that dominates the city to the east and protects access to the isthmus of Cabrero. Within the protective security of the city’s defensive walls are the historic centre’s three neighbourhoods: Centro, the location of the Cathedral of Cartagena, the Convent of San Pedro Claver, the Palace of the Inquisition, the Government Palace and many fine residences of the wealthy; San Diego (or Santo Toribio), where merchants and craftsmen of the middle class lived; and Getsemaní, the suburban quarter once inhabited by the artisans and slaves who fuelled much of the economic activity of the city.

Historic Centre of Santa Cruz de Mompox

Historic Centre of Santa Cruz de Mompox

Santa Cruz de Mompox, located in the swampy inland tropics of northern Colombia’s Bolívar Department, was founded about 1539 on the Magdalena River, the country’s principal waterway. Mompox was of great logistical and commercial importance, as substantial traffic between the port of Cartagena and the interior travelled along the river. It consequently played a key role in the Spanish colonization of northern South America, forming an integral part of the processes of colonial penetration and dominion during the Spanish conquest and of the growth of communications and commerce during the 17th to early 19th centuries. The city developed parallel to the river, its sinuous main street growing freely and longitudinally along the river bank, on which barricade walls (albarradas) were built to protect the city during periods of flooding. Instead of the central plaza typical of most Spanish settlements, Mompox has three plazas lined up along the river, each with its own church and each corresponding to a former Indian settlement. Most of the buildings in its 458-ha historic centre are in a remarkable state of conservation and still used for their original purposes, thus preserving an exceptional illustration of a Spanish riverine settlement. Founded in 1540 on the banks of the River Magdalena, Mompox played a key role in the Spanish colonization of northern South America. From the 16th to the 19th century the city developed parallel to the river, with the main street acting as a dyke. The historic centre has preserved the harmony and unity of the urban landscape. Most of the buildings are still used for their original purposes, providing an exceptional picture of what a Spanish colonial city was like.

The historic centre of Santa Cruz de Mompox’s identity as a Spanish colonial river port defines the unique and singular character of its monumental and domestic architecture. From the 17th century onwards, houses were built on the Calle de La Albarrada with the ground floors given over to small shops. These “house-store” buildings are built in rows of between three and ten units. Significant in their contribution to the townscape are the open hallways across the front facades that share a common roof. The private houses of the 17th to early 19th centuries are laid out around a central or lateral open space, creating linked environments adapted to the climate and reflecting local customs. The earliest type of house for merchants or Crown servants has a central courtyard; there is often a secondary courtyard for services attached to the back of the building. Most of the houses retain important features such as decorated portals and interiors, balconies and galleries. The special circumstances of the development of the city along the river have given it a quality with few parallels in this region. Its economic decline in the 19th century conferred a further dimension on this quality, preserving it and making it the region’s most outstanding surviving example of this type of riverine urban settlement.

Los Katíos National Park

Los Katíos National Park

Los Katíos National Park has great biological wealth and a privileged role in the South American continent’s biogeographical history. Contiguous to the much larger Darién National Park of Panama which is also a World Heritage Site, these two areas together protect a representative sample of one of the world’s most species-rich areas of moist lowland and highland rainforest, with exceptional endemism. Extending over 72,000 hectares in north-western Colombia, the park is located in the Colombian mountain zone up to an elevation of 600m and encompasses significant wetland areas, including the extensive Ciénagas de Tumaradó. It is the only place in South America where a large number of Central American species occur, including threatened species such as the American Crocodile, Giant Anteater and Central American Tapir.

San Agustín Archaeological Park

San Agustín Archaeological Park

The San Agustín Archaeological Park is located in the Colombian Massif of the Colombian southwestern Andes, on terrains of the municipalities of San Agustín and Isnos, in the department of Huila. Three separate properties, totalling 116 ha, comprise the Archaeological Park: San Agustín (conformed by the Mesita A, Mesita B, Mesita C, La Estación, Alto de Lavapatas and Fuente de Lavapatas sites), Alto de los Ídolos and Alto de Las Piedras. The park is at the core of San Agustín archaeological zone featuring the largest complex of pre-Columbian megalithic funerary monuments and statuary, burial mounds, terraces, funerary structures, stone statuary and the Fuente de Lavapatas site, a religious monument carved in the stone bed of a stream.

The ceremonial sites are at the centre of settlement concentrations and contain large burial mounds connected to one another by terraces, paths, and earthen causeways. The earthen mounds, some measuring 30 m in diameter, constructed during the Regional Classic period (1-900 AD) covered large stone tombs of elite individuals of the well documented chiefdom societies that developed in the region since around 1000 BC–one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The tombs contain an elaborate funerary architecture of stone corridors, columns, sarcophagi and large impressive statues depicting gods or supernatural beings, an expression of the link between deceased ancestors and the supernatural power that marks the institutionalization of power in the region. In the municipality of San Agustin the main archaeological monuments are Las Mesitas, where the ancestors constructed artificial mounds, terraces, funerary structures and stone statuary; the Fuente de Lavapatas, a religious monument carved in the stone bed of a stream; and the Bosque de Las Estatuas, where there are examples of stone statues from the whole region. The Alto de Los Idolos is on the right bank of the Magdalena River and the smaller Alto de las Piedras lies further north: both are in the municipality of San José de Isnos. Like the main San Agustín area, they are rich in monuments of all kinds. Much of the area is a rich archaeological landscape, with evidence of ancient tracks, field boundaries, drainage ditches and artificial platforms, as well as funerary monuments. This was a sacred land, a place of pilgrimage and ancestors worship. These hieratic guards, some more than 4 m high weighing several tonnes, are carved in blocks of tuff and volcanic rock. They protected the funeral rooms, the monolithic sarcophagi and the burial sites.

The monuments are located at the political and demographic centers of chiefdom societies that consolidated their power through complex ceremonial activities and the production of knowledge. San Agustín chiefdoms and the outstanding statuary of their tombs represent an exceptional trajectory of political centralization amidst a rugged environment and without the concentration of economic wealth, and as such are of great scientific and aesthetic importance.

National Archeological Park of Tierradentro

National Archeological Park of Tierradentro

The National Archaeological Park of Tierradentro is located in the south-western of Colombia in Andean’s central cordillera, in the municipality of Inzá, department of Cauca. Four areas, dispersed over a few square kilometres, make up the archaeological park: Alto de San Andrés, Alto de Segovia, Alto del Duende, El Tablón and as a site of importance but outside the park boundary the Alto del Aguacate. The park contains all known monumental shaft and chamber tombs of Tierradentro culture, the largest and most elaborate tombs of their kind.

The area holds the largest concentration of pre-Columbian monumental shaft tombs with side chambers–known as hypogea—which were carved in the volcanic tuff below hilltops and mountain ridges. The structures, some measuring up to 12 m wide and 7 m deep, were made from 600 to 900 AD, and served as collective secondary burial for elite groups. The degree of complexity achieved by the architecture of these tombs with chambers that resemble the interior of large houses is evident in the admirable carving in tuff of the stairs that give access to a lobby and the chamber, as well as in the skilful placement of core and perimeter columns that required very careful planning. The tombs are often decorated with polychrome murals with elaborate geometric, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic designs in red and black paint on a white background, and the chambers of the more impressive underground structures were also decorated with elaborate anthropomorphic carvings. The smaller hypogea vary from 2.5 m to 7 m in depth, with oval floors 2.5-3 m wide, while the chambers of the largest examples may be 10-12 m wide. Most impressive of the latter are those with two or three free-standing central columns and several decorated pilasters along the walls with niches between them.

The symbolic symmetry achieved between the houses of the living above ground and the underground hypogea for the dead, by means of a limited but elegant number of elements, not only conveys an aesthetic sensation but also evokes a powerful image of the importance of a new stage into which the deceased has entered and the continuity between life and death, between the living and the ancestors.

The present state of archaeological and anthropological knowledge suggests that the builders of the hypogea (underground tombs) lived in the mountain slopes and valleys in the area. In the valleys they established small settlements whereas on the hillsides settlement was dispersed, close to the fields. The oval-plan residential sites were built on artificial terraces, with rammed earth floors. The wooden frames were filled with wattle-and-daub and the roofs were thatched. There were no internal divisions and there was a single combustion zone, with wooden benches for sleeping. The magnitude of the underground works and the way in which human remains were disposed inside the hypogea indicate the existence of a hierarchical social and political structure based on chiefs with priestly functions. The stone statues of the Tierradentro region are of great importance. They are carved from stone of volcanic origin and represent standing human figures, with their upper limbs placed on their chests. Masculine figures have banded head-dresses, long cloths and various adornments whereas female figures wear turbans, sleeveless blouses and skirts. There are feline and amphibious representations manifested in sculptures.

Underground tombs with side chambers have been found over the whole of America, from Mexico to north-western Argentina, but their largest concentration is in Colombia. However, it is not only the number and concentration of these tombs at Tierradentro that is unique but also their structural and internal features.

Qhapaq Ñan, Andean Road System

Qhapaq Ñan, Andean Road System

Qhapaq Ñan, Andean Road System is an extensive Inca communication, trade and defence network of roads and associated structures covering more than 30,000 kilometres. Constructed by the Prehispanic Andean communities over several centuries, the network reached its maximum expansion in the 15th century, during the consolidation of the Tawantinsuyu, when it spread across the length and breadth of the Andes. The network is based on four main routes, which originate from the central square of Cusco, the capital of the Tawantinsuyu. These main routes are connected to several other road networks of lower hierarchy, which created linkages and cross-connections. 137 component areas and 308 associated archaeological sites, covering 616.06 kilometers of the Qhapaq Ñan highlight the achievements of the Incas in architecture and engineering along with its associated infrastructure for trade, storage and accommodation as well as sites of religious significance. The road network was the outcome of a political project implemented by the Incas linking towns and centers of production and worship together under an economic, social and cultural programme in the service of the State.

The Qhapaq Ñan, Andean Road System is an extraordinary road network through one of the world’s most extreme geographical terrains used over several centuries by caravans, travellers, messengers, armies and whole population groups amounting up to 40,000 people. It was the lifeline of the Tawantinsuyu, linking towns and centres of production and worship over long distances. Towns, villages and rural areas were thus integrated into a single road grid. Several local communities who remain traditional guardians and custodians of Qhapaq Ñan segments continue to safeguard associated intangible cultural traditions including languages.

The Qhapaq Ñan by its sheer scale and quality of the road, is a unique achievement of engineering skills in most varied geographical terrains, linking snow-capped mountain ranges of the Andes, at an altitude of more than 6,600 metres high, to the coast, running through hot rainforests, fertile valleys and absolute deserts. It demonstrates mastery in engineering technology used to resolved myriad problems posed by the Andes variable landscape by means of variable road construction technologies, bridges, stairs, ditches and cobblestone pavings.

Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary

Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary

Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary is a large marine protected area some 500 km off Colombia’s Pacific Coast. The terrestrial area of 35 hectares, the barren Malpelo Island and its rocky outcroppings, represents the highest elevation of the enormous underwater Malpelo Ridge. Despite its small size the island is believed to play an important role as an aggregation point for the reproduction of numerous marine species. The vast majority of the property, 857,465 hectares, is a “marine wilderness” constituting the largest no-fishing zone in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. The rugged underwater topography includes steep walls, caves and tunnels, reaching a depth of around 3,400 metres. Jointly with the local confluence of several oceanic currents, this complex terrain is the basis for highly diverse marine ecosystems and habitats. Due to the remoteness and protection efforts the conservation status of the property is excellent, making Malpelo one of the top diving destinations in the World. Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary belongs to the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor, a marine conservation network, which also includes World Heritage properties in Costa Rica, Ecuador and Panama.

The property hosts impressive populations of marine species, including large top predators and pelagic species, such as Giant Grouper, Billfish and numerous shark species. Major aggregations of Hammerhead Shark, Silky Shark, Whale Shark and Tuna have been recorded. Other biodiversity highlights include 17 marine mammal species, seven marine reptile species, 394 fish species and 340 species of mollusks. Known marine endemics include five fish species and two sea star species. Malpelo Island and its satellite rocks boast a limited but highly specialized terrestrial biodiversity characterized by a high degree endemism, including five plant species, three reptiles and two arthropods. The rocky outcroppings support large colonies of Nazca Boobies, as well as important populations of Swallow-tailed Gull, Masked Booby and the critically endangered Galapagos Petrel.

Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia

Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia

The Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia (CCLC) is a continuing productive landscape consisting of a series of six sites, which integrate eighteen urban settlements. The property illustrates natural, economic and cultural features, combined in a mountainous area with collaboratively farmed coffee plantations, some of these in clearings of high forest.

The CCLC is the result of the adaptation process of Antioquian settlers, who arrived in the 19th century, a process which persists to this day and has created an economy and culture deeply rooted in the coffee production tradition. Coffee farms are located on steep mountains ranges with vertiginous slopes of over 25% (55 degrees), characteristic to the challenging coffee terrain. These unusual geographic features also affect the small orthogonal plot layouts, and influence the architectural typology, lifestyle and land-use techniques of the cafeteros (coffee farmers). The distinctive way of life of the cafeteros is based on legacies that have been passed down from generation to generation, and is linked to their traditional landownership and the distinctive small farm production system.

The typical architecture in the urban settlements is a fusion between the Spanish cultural patterns and the indigenous culture of the region adapted as well to the coffee growing process, through for example their sliding roofs. Houses function as both dwelling units and centers of economic activity, with walls built in the traditional, more flexible and dynamic ‘bahareque’ constructive system, and covered by a layer of bamboo well known for its resistance and malleability. Over fifty percent of the walls are still built using this traditional method.

Chiribiquete National Park – “The Maloca of the Jaguar”

Chiribiquete National Park – The Maloca of the Jaguar

Chiribiquete National Park – “The Maloca of the Jaguar” is in the Amazon rainforest in south central Colombia. Following its extension in 2013, the park is now the largest national park in Colombia at 2,782,354 hectares and is very large by global standards for protected areas. It is located at the western-most edge of the Guiana Shield and contains one of only three uplifted areas of the Shield called the Chiribiquete Plateau. One of the most impressive defining features of Chiribiquete is the presence of many tepuis which are table-top mountains, found only in the Guiana Shield, notable for their high levels of endemism. The tepuis found in Chiribiquete, whilst smaller when compared to others in the Guiana Shield, result nonetheless in dramatic scenery that is reinforced by their remoteness and inaccessibility. A particularly significant value of the property is its high degree of naturalness which makes it one of the most important wilderness areas in the world.

Some 75,000 rock pictographs have been listed on the walls of 60 rock shelters at the foot of tepuis. The portrayals are interpreted as scenes of hunting, battles, dances and ceremonies, all of which are linked to a purported cult of the jaguar, seen as a symbol of power and fertility. Such practices are thought to reflect a coherent system of thousand-year-old sacred beliefs, organizing and explaining the relations between the cosmos, nature and man. The archaeological sites are believed to be accessed even today by indigenous uncontacted groups.

Chiribiquete is home to many iconic species including Jaguar, Puma, Lowland Tapir, Giant Otter, Howler Monkey, Brown Woolly Monkey. A high level of endemism occurs in the property and the number of endemic species is likely to rise substantially once new research programmes are implemented.

The global significance of the property to biodiversity conservation is reflected by the fact that it is considered a Centre of Plant Diversity, an Important Bird Area, an Endemic Bird Area, a Key Biodiversity Area and it is the only site protecting one of the terrestrial ecoregions of flooded forests called “Purus Varze”, considered Critical/Endangered by WWF International. The biodiversity values of the property are inextricably linked to its significant cultural and archaeological values that are strongly associated to the beliefs and spiritual values of the indigenous peoples living in the property.

Tours & Tickets in Colombia

| COLOMBIA TRAVEL GUIDE |

| Related Articles |

If you’re travelling to Colombia, we help you:

![]() General Information About Colombia: National symbols of Colombia – Colombia: living history – Geography of Colombia – Economy of Colombia – Languages of Colombia

General Information About Colombia: National symbols of Colombia – Colombia: living history – Geography of Colombia – Economy of Colombia – Languages of Colombia

![]() Practical information about Colombia: Climate – How to get to Colombia – Visa, Customs, Documentation and Taxes – Embassies and consulates in Colombia – Health and vaccination – Emergency numbers – Culture of Colombia – Measures and Electricity – Currency of Colombia

Practical information about Colombia: Climate – How to get to Colombia – Visa, Customs, Documentation and Taxes – Embassies and consulates in Colombia – Health and vaccination – Emergency numbers – Culture of Colombia – Measures and Electricity – Currency of Colombia

![]() Tourist Information about Colombia: General Information – Practical information about Colombia – Adventure Colombia – Hotels and accommodations in Colombia – How to Get to Colombia – Gastronomy in Colombia – Colombia’s Best Festivals and Carnivals – Tourist Attractions in Colombia – Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Colombia – Tips and advice for travel in Colombia – Top 10 Colombian Travel Destinations – Natural regions of Colombia – Cultural Tourism in Colombia – UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists – UNESCO Heritage Sites in Colombia – Top 10 amazing places to visit in Colombia – Colombian Cuisine – Tourism of Nature

Tourist Information about Colombia: General Information – Practical information about Colombia – Adventure Colombia – Hotels and accommodations in Colombia – How to Get to Colombia – Gastronomy in Colombia – Colombia’s Best Festivals and Carnivals – Tourist Attractions in Colombia – Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Colombia – Tips and advice for travel in Colombia – Top 10 Colombian Travel Destinations – Natural regions of Colombia – Cultural Tourism in Colombia – UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists – UNESCO Heritage Sites in Colombia – Top 10 amazing places to visit in Colombia – Colombian Cuisine – Tourism of Nature

![]() Travel Guide of Colombia: Colombia Travel Guide – Amazonas – Antioquia – Arauca – Atlántico – Bolivar – Boyacá – Caldas – Caquetá – Casanare – Cauca – Cesar – Chocó – Córdoba – Cundinamarca – Guanía – Guaviare – Huila – La Guajira – Magdalena – Meta – Nariño – Norte de Santander – Putumayo – Quindio – Risaralda – San Andrés y Providencia – Santander – Sucre – Tolima – Valle del Cauca – Vaupés – Vichada

Travel Guide of Colombia: Colombia Travel Guide – Amazonas – Antioquia – Arauca – Atlántico – Bolivar – Boyacá – Caldas – Caquetá – Casanare – Cauca – Cesar – Chocó – Córdoba – Cundinamarca – Guanía – Guaviare – Huila – La Guajira – Magdalena – Meta – Nariño – Norte de Santander – Putumayo – Quindio – Risaralda – San Andrés y Providencia – Santander – Sucre – Tolima – Valle del Cauca – Vaupés – Vichada

Flights, Cheap Airfare Deals & Plane Tickets |